The prayers for the Jewish Passover meal begin with this question, asked by the youngest person present, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” It implies that this religious ritual is unique, not just another Sabbath or feast day, but it has a particular resonance, even after 3300 or so Passovers in history. Passover calls the guests to participate in the change that God is bringing. Expecting something genuinely different than the status quo is hard to come by. Think of all the phrases that all mean nothing changes:

· Business as usual.

· Nothing new under the sun.

· Déjà vu.

· Stuck in a rut.

· Like a broken record.

· Same old, same old.

· It is what it is.

· Ground Hog Day.

Our language offers a rich variety of ways to accept the inevitability of fate and failure. But Passover is meant to be unlike any other time, where we hope for an inflection point of things becoming different.

· We experience Jamais vu, something we have never seen before.

· A broken record can also mean a new feat of excellence.

· Instead of being stuck in a rut, we blaze a new trail.

· Behold, says God, I am making all things new.

· This is the day the Lord has made; let us rejoice and be glad.

Today’s lectionary, Exodus 14, has jumped 11 chapters from Moses at the burning bush. Moses confronted Pharoah, and he was not only rejected, but things also got worse for the Israelites. Pharoah punished them by forcing them to make bricks without straw, increasing their workload—business as usual. Passover comes after nine plagues, with infestations of frogs, lice, and flies, then boils, hail, and locusts. The Nile turns the color of blood, basically a summer in Florida. After each plague, Pharoah hardens his heart and will not relent to end enslavement. What will it take for Egypt to realize that injustice and inhumanity are causing instability? But how would the Egyptians look at us as we keep calling climate change a hoax and think we have achieved a post-racial society of equality?

Passover is the last terrible plague where first-born Egyptians are struck dead in the night. It all sounds horrific, but remember Moses is the only male his age who survived the genocide by Pharoah of all Hebrew male children. The ten plagues may make God seem like a vengeful and angry God, but the Egyptian suffering still may be less than the inhumanity of slavery. Plus, they have a way out, repent, and do justice. But they can’t imagine a different world where they run an economy without slavery. They may hate operating it, but it is what it is.

Our text focuses on what the Israelites must do. The author pauses the suspenseful story to insert instructions on liturgy for all future Passovers. It prescribes a feast to remember the suffering and liberation, eating bitter herbs of Haroset, dipping vegetables in salt water to remember the tears, eating unleavened bread because there was no time to bake bread since the people had to be ready to move. They would take unleavened bread, which could last seven days while on the move, crossing the Red Sea and out of Egypt. The author wants to show that this moment in history is so critical that it deserves re-enacting every year so people don’t forget where they came from, who God is, and the goodness God wants for humanity. We lose touch with energy and wisdom when we forget our origins. In forgetting, we can become complacent, arrogant, or disheartened. Remembering revitalizes us.

What better way to remember than having a sacred meal, with the rituals to tell the story again? I thought of this while entertaining old friends I’ve known since the 1990s. We did many things last weekend, kayaking and walking through the Botanical Gardens, but the best part was dinner. We talked deep into the night as the wine bottle slowly emptied and told all the old stories we knew together. We remembered all we had come through, where we stand today, and what we value. When they left, we all felt renewed and grounded. This grounding is what the Passover can do or what communion does in our context. We tell the old, old story of how we overcame adversity. Life is not the same old, same old.

Passover is the inflection point where slavery ends, and a new life begins. But this new reality comes with new challenges. God does not teleport people from Egypt to the Promised Land. The Egyptians don’t suddenly become friends and create a just and equal society for the Israelites. The people must get up, take what they can carry, and leave the rest behind. We know they have much ahead of them, crossing the Red Sea and forty years of being nomads in the wilderness. But it all starts with the first steps and leaving behind a life that is not working.

Many of you have made a transition in the past. You had to leave home, a marriage, a job, or even a church that was stifling your soul. We can get so accustomed to a bad situation that it is hard to believe another life is possible. Leaving is a leap into the unknown. I will never forget the day I decided to move out as my first marriage ended. I could only afford a crappy, one-bedroom, fourth-floor walkup in a bad neighborhood. I met the landlord on an oppressively hot day. As I handed him the cash security deposit, I began to weep. The landlord looked like a guy from central casting who would play a slum lord. He looked at me crying, gave me a sweaty hug, patted my back, and said, “There, there.” It was the low point of my life to that moment. I could not imagine a greater embarrassment than the feeling of failing everyone: my wife and family and my church.

With twenty years of hindsight, I can see that was the inflection point. I tried hard to pretend my life was working when it was not. Nothing good in my life now would exist without that first step. A decisive moment does not always feel like liberation. It can feel like shame and failure. Our text does not tell us what the Israelites felt at Passover. But the ritual begins with a somber tone of remembered suffering. It does not sound like they left Egypt rejoicing. They knew they were stepping into an uncertain future with hardship ahead. They carried the grief of loss into their new life. In the wilderness, they longed for the certainty of the past, even if it had been a hard life. Their grief did not disappear when they fled, but over time, they learned resilience and built a new life.

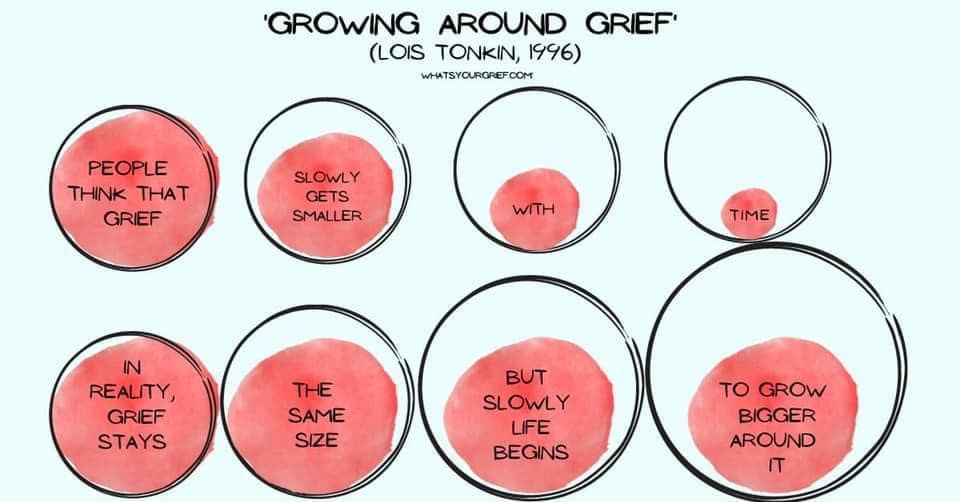

Greif is a sticky thing. Even as life gets better, it does not leave us. People talk about grief like it will shrink and eventually pass, but that isn’t how it works. I saw a meme this week that crystallized what I had not put in words before.

Greif does not lose its power by shrinking. Greif may never lose its energy or content, but the feelings change as our soul grows. Over time, we produce a new sense of self, almost like growing a new skin. We develop a larger emotional body and a wise soul with more capacity. The circle of our awareness and understanding grows larger.

I think this graphic illustrates that if we want something new to happen, we must grow our souls. It takes more than deciding to do something different. I have decided dozens of things that never happened. We might want to write a book, start a new business, learn to paint, look for a new relationship, get training, or start school. But it always requires leaving something behind. The hardest part of a new beginning is letting go of our old selves and welcoming what we might become before we know what it is.

I think this is a significant element of the whole Exodus story. Change requires letting go of the past to move into the new, and this will reshape our souls in ways we don’t know till we get there. No wonder the same old, same old, has so much power over us.

When God works in our lives, it doesn’t suddenly transform our situation like a lightning bolt. We don’t wake up to find a miracle has made our lives what we always wanted. The miracle is God makes a way where we thought there was no way. We find an open door we expected to be locked. But we still must walk through the door into the uncertain, frightening and possibly wondrous future.

Exodus is a story of moral courage. From the burning bush, to Passover, to next week’s scripture on getting though the Red Sea, this gives us a landscape of the spiritual journey. God makes a way where we thought there was no way.